Global tertiary education and the fourth industrial revolution

It is an exciting time to work in the global education sector. Technology is changing the world around us and the digital age is challenging traditional models of learning and teaching. Our current education systems were designed for a different era – one which sought standardisation and which offered students a one-size-fits-all experience.

The ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ means the expectations of today’s students are different and that the skills that today’s graduates will need to be successful in our new economies will also be different.

So, where are we now in this transformation and on what future work skills should we focus? And how can public and private sector institutions, including government and industry, work together to help manage this transition successfully?

Digital disruption – where are we now?

In late 2017 Navitas Ventures launched its first Digital Transformation in Higher Education Report. This global study gathered perspectives on digital transformation from across our sector, including from 26 university leaders, 100 recent university graduates, and 42 founders of education startups who are at the forefront of driving change.

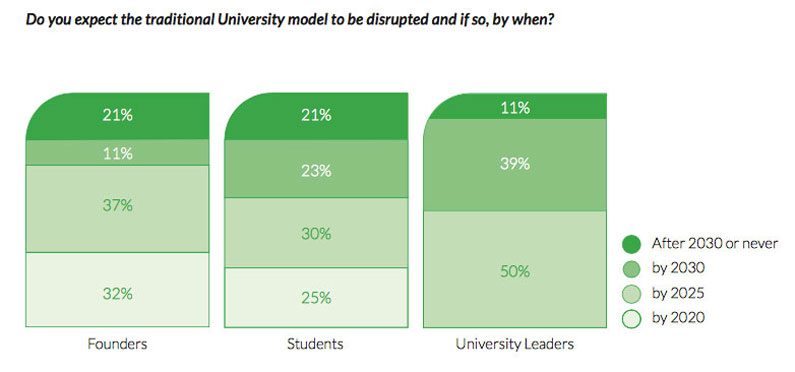

The study showed that we can expect disruption in the next decade. At least 50 per cent of respondents see the traditional university model being disrupted by 2025. Students and EdTech entrepreneurs expect the time frame to be even shorter, with approximately one in four expecting disruption within the next two to three years. While universities expect disruption to take longer, nine out of ten Vice Chancellors nonetheless expect the university model to be disrupted by 2030 – when this year’s six-year-old children will be starting university.

The research also suggests that higher education transformation is already underway. Every university surveyed indicated they are at least part way through their digital journey and that these programs were being led by an operational leader – that is, either a vice president, deputy vice chancellor or provost.

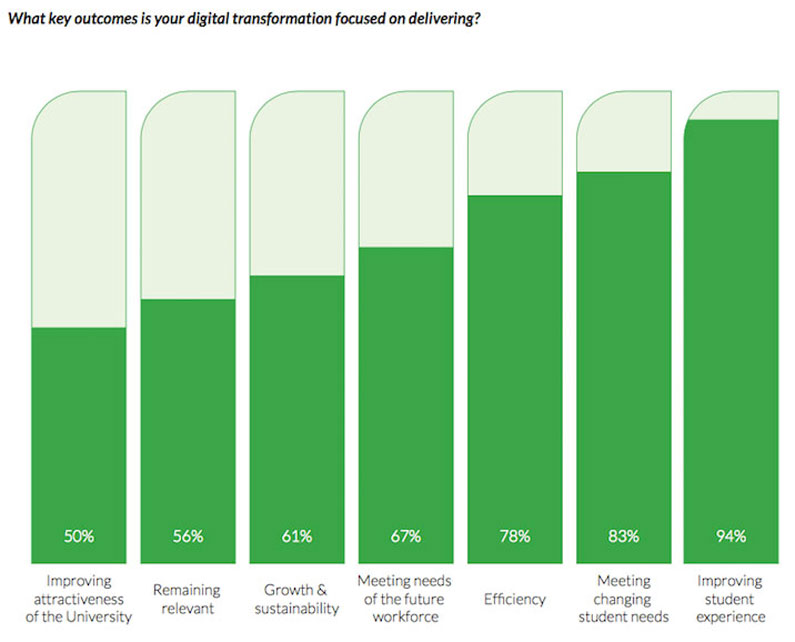

However, university leaders, EdTech founders and students have divergent views when it comes to priorities for change. University leaders view digital transformation as a way to improve rather than replace their traditional models. Around 75 per cent plan to partly digitise their current operations, with few aiming to create new digital models or to fully digitise their current model. Further, current university transformation programs seem largely focused on the foundations of the learning experience, in areas such as administrative efficiency and digitised learning content.

By contrast, learners are more concerned with their immediate employment prospects on graduation, identifying innovations and technologies that support pathways to employment to be their highest priority. It is our observation that EdTech founders have already recognised this and are responding with their own solutions.

The changing world of work and the learner of the future

The changing world of work means more demand for retraining and the need for education to focus on new skill sets aligned to future jobs. A good example is right here in Australia, where we are seeing a shift away from resources and other heavy industries towards more knowledge-intensive industries aimed at capturing the continued development of economies in Asia.

So what are the skills required for these future jobs and industries? A recent report by Alpha Beta and the Foundation for Young Australians identified a new set of essential enterprise skills – also referred to as 21st century skills. These transferable skills are not role- or industry-specific, but enduring capabilities such as problem solving, financial literacy, digital literacy, teamwork, communication, creativity, critical thinking and presentation skills.

Examples of progress

There are already many examples of progress to meet these changing expectations of students.

Minerva is an education technology startup established in 2014 that delivers an innovative and proprietary undergraduate program, combining online courses and experiential learning. The Minerva program offers classes as seminars rather than lectures, with more focus on student experience, participation and engagement rather than one-way delivery of curriculum. Classes are capped at 20 students and learners are assessed on their participation and thinking abilities rather than through exams.

Another example is Deakin University in Australia, which is using micro-credentialling to meet the increasing need for reskilling in a way that’s flexible, portable and personalised.

Deakin established DeakinCo with the aim of building purpose-built learning, development and measurement solutions for the future. At the heart of this is an acknowledgement that many of today’s workforce don’t have the time or the resources to undertake education and training in a linear, traditional model.

DeakinCo introduced a suite of independently verified micro-credentials to help professionals develop and certify their skills, knowledge and experience in ‘softer’ skill areas, such as communication, teamwork, critical thinking and professional expertise.

These micro-credentials – which are like mini-degrees or certifications in a specific area of work – are offered online and on demand. Assessment is competency-based, focused on checking student understanding and collecting evidence through work completed in employment.

The program helps to recognise the informal learning that professional employees do in their day-to-day work. In addition to being more flexible than traditional study, for participants, these micro-credentials make reskilling, professional development and career advancement easier.

For employers, micro-credentialling helps validate employee competencies and skills beyond the academic accomplishments of a more formal higher education. It is also an effective engagement tool, allowing organisations to develop an ‘always learning’ culture to recognise and reward staff.

The role of governments and industry

Governments and industry must also play a role as our sector continues to transition.

Government must continue to support the development of a diverse, competitive, learner-centred tertiary system. In Australian, the introduction and extension of the demand-driven system for undergraduate places is one example of an early shift in this direction. Until recently, we also had seen an attempt to increase access to vocational sector education.

Governments must allow students to refresh or top up their loan banks as debt is repaid and come up with new ways to ensure access to reskilling linked to employment outcomes.

Government or private sector funding and loan support can also help support the uptake of new education models and technologies. Given increasing constraints on public funding, it is in the government’s interest to encourage the uptake of new education technologies that can achieve more with less.

Malaysia is one country that has introduced a number of initiatives to create an inclusive, agile, progressive and competitive higher education system.

This includes an accreditation and prior experiential learning program as a pathway to Malaysian universities, a credit recognition and transfer policy for Massive Open Online Courses, and a work-based learning initiative to redefine traditional education and improve graduate employability.

This last initiative underlines just how critical industry is to helping us meet the challenges we face. We must do more to engage and listen to the business community to ensure our programs match future skills needs and emerging sectors.

A call to action

While education and skilling should always be grounded in sound pedagogy – involving constructing and delivering content to learners with the aim of developing and recognising knowledge, skills and competency – the courses we develop, the skills we focus on, and the way we interact and deliver to students will and must all change as technology continues to evolve.

Our best response will be to come together as a sector and to work in partnership to develop solutions that will improve access and outcomes to ensure graduates are work ready and world ready.

The proliferation of university pathway programs around the world is a good example of how our sector has worked together previously to innovate and overcome challenges to improve student outcomes.

Back in 1994, we saw an opportunity to partner with universities to support international students to transition into their degree with targeted English language, academic and welfare support. We knew the high failure rates for international students coming to Australia had nothing to do with academic ability but were a result of language barriers, transitional issues and the challenges of learning in a Western higher education environment.

This pathway model was part of a wave of innovation brought about through public-private partnerships. It came at a time when our sector was energised to take advantage of the significant opportunities presented in international education.

The global success of this university pathway model is a great lesson in what can be achieved when different parts of our sector work closely together. I believe a similar level of collaboration is required for us to meet the challenges and opportunities facing us in this new era.

This piece is an excerpt from a keynote address given at the 2017 AFR Higher Education Summit.