Why India won’t be the next China

University strategy offices globally have long speculated over India’s potential to become the ‘next China’. With international students from India set to pass those from China as the largest cohort of international students in Australia and enrolling in record numbers in Canada, are we now at an inflexion point? Will India develop into ‘China 2.0’, or continue to chart its own course?

Key differences: by the numbers

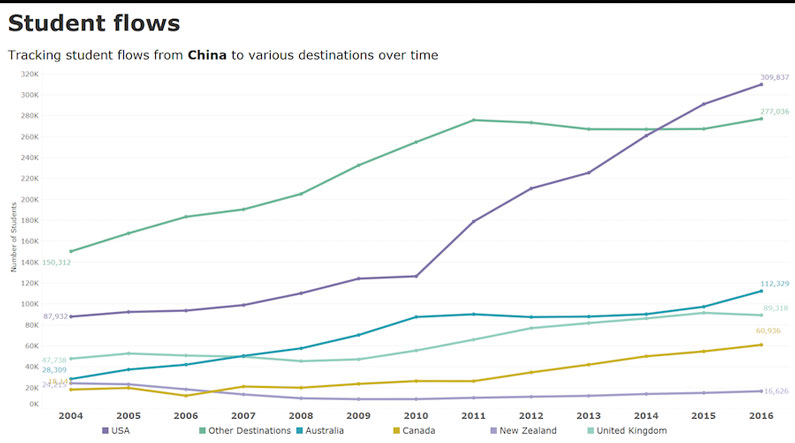

Since the dramatic increase in students studying abroad from the early 2000s, China has been the stand-out source of international enrolments for major English speaking destinations including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. New learning models, from full degree study abroad and articulation agreements to in-country delivery and online learning reflect China’s strategic importance for many leading educational institutions.

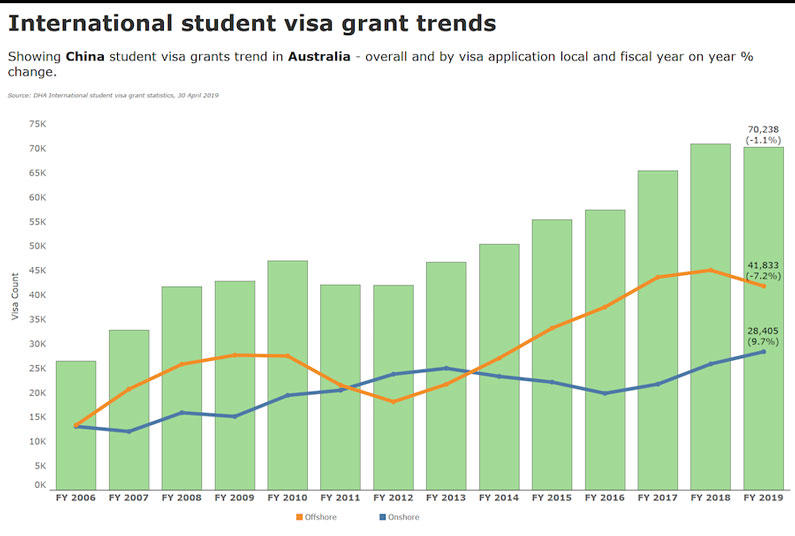

UNESCO’s most recent estimates (there is a lag here – the most recent comparable data for all destinations is from 2016) suggest there are 870,000 Chinese students studying abroad – a number still far ahead of India at 305,000. It is unlikely in the short (or even medium) term that India will overtake China globally – but with Chinese enrolments now stagnating (or in decline) for some destinations, many providers are looking to other fast-growing global markets.

CHINA FLOWS

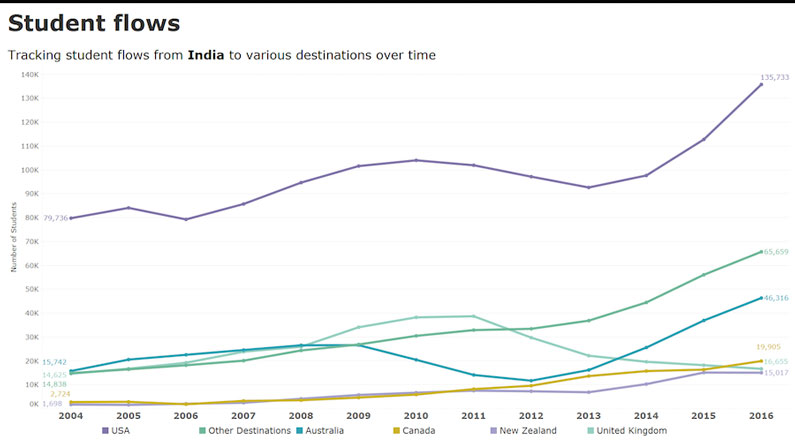

India is far from a truly ‘emerging market’; overall volumes have been growing for over a decade – however the extent of growth over the past three years demands fresh analysis.

INDIA FLOWS

The US has historically dominated the Indian student market. However, other Western countries are experiencing an increased share. Rather than steady growth for destinations like the UK, Canada and Australia, changes in market share have fluctuated significantly depending on visa and post-study work policies. As destination countries tweak these settings, Indian students and their parents respond quickly. The UK’s growth in market share (from historical averages of 6%) in 2006 to 10% in 2011 coincided with extension to post study work rights – whilst the subsequent rapid decline was tied to the removal of same work rights.

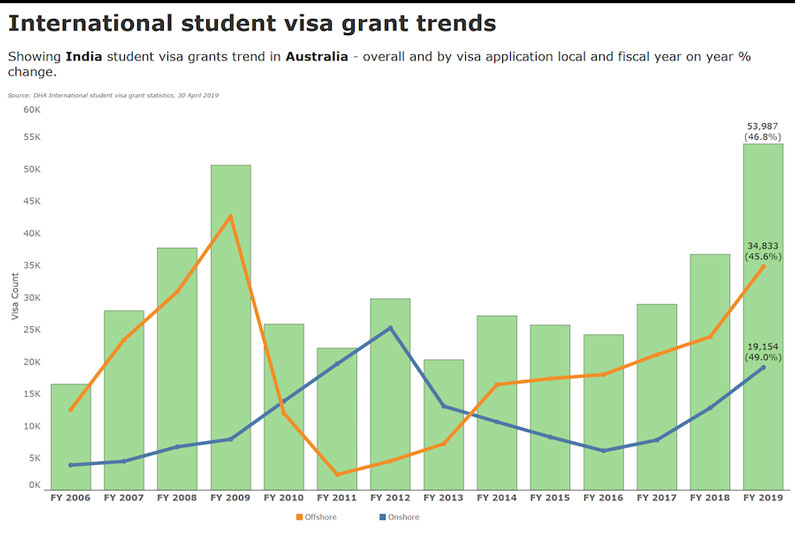

More recent visa grant data is available for destination Australia – and it is worth of inclusion here to demonstrate the rapid acceleration in student numbers continuing from India.

INDIA VISA TRENDS

CHINA VISA TRENDS

Forces driving difference

Choice of location and study area

At Navitas, we are seeing that Indian students tend to enrol across a wider range of institutions and geographic locations and are significantly more likely to study in a regional (or non-capital) city than their Chinese counterparts. Anecdotal evidence suggests they are attracted by community support in a diaspora, lower cost of living, employment opportunities, and links to temporary or permanent migration.

In contrast, recent growth in Chinese numbers has been concentrated in postgraduate studies in Russell Group institutions (UK), the east coast members Australia’s Go8 (Group of 8) and similarly ranked universities in New Zealand, Canada and the US.

Our enrolment data also suggests Indian students tend to study STEM subjects, although demand for business, management and to a lesser extent health has grown to rival traditional IT or engineering degrees. There is also more significant demand for vocational skills than amongst other major markets, and less demand for high school study than from China.

Investing in education, with expectation of return

Like their fellow students from China, most Indian students pay their fees using private funds rather than state sponsorship. However, a substantial proportion of funding comes through bank loans – often secured against property. The nature of this investment goes some way to explain the appetite for post-study work and in-study work opportunities. It is not unusual for a family in India’s burgeoning middle class to have several children studying abroad.

Preference for an international experience

The majority of Indian students seeking a foreign qualification currently travel to a destination country for the entirety of their study. There is limited in-country or trans-national delivery, given regulation prohibits the establishment of branch campuses or articulation/twinning arrangements. India’s 2019 National Education Policy indicated these barriers could be relaxed – but this has not yet been realised.

Desire to work post-study

There is a clear link between study and temporary migration for employment amongst Indian students. The experience gained – and income derived – from this employment is important to offset the family’s investment and help repay their study loans.

Schemes such as Fresh Talent, Working in Scotland and the introduction of post-study work in Canada have sought international competitive advantage over other destinations. Demand is also shifting beyond the traditional destination countries. Currently Russia, UAE and the Ukraine offer specialist qualifications such as medicine at a significantly lower cost and with less visa red tape.

New competition emerging for the Indian market

With continued population growth and an increasing GDP, the demand for international education from India will continue to increase. As destination countries seek to diversify from China as the key source market, India will become more important. If regulations for in-country delivery in India are relaxed as anticipated, we are likely to see twinning arrangements and branch campuses emerge. India is then likely to emerge as a regional hub – with qualifications ranging from vocational through higher education, awarded by newly emerging countries in the international education ecosystem.

Indian students and their parents demonstrate different purchasing and selection criteria than their Chinese counterparts. They are more likely to study in new or emerging destinations (regional cities in established destination countries – or new destinations entirely), more likely to study vocational courses and use a wider set of criteria when choosing their preferred study destination, many of which relate to employment opportunities. This market offers significant opportunity for a range of destinations and providers – although historically at a greater risk of cyclical fluctuations and subject to “boom and bust”.

India is then likely to emerge as a regional hub – with qualifications ranging from vocational through higher education, awarded by newly emerging countries in the international education ecosystem. Providers and destinations not already successful in India will need to adapt to this market – as India (and other similar emerging source markets) will provide the growth opportunities to drive the next wave of international recruitment.